Motions of the mind

In 1435, Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise "On Painting" established a set of fundamental requirements for the creation of narrative art. The portrayal of the figure according to its inner feelings and emotional state was of paramount importance. Expressions, gestures and motions should all be potent and declamatory, like those of an orator. Alberti’s advice became a creed and manifesto for Leonardo, which he took to new heights. Man must be portrayed as a dynamic, responsive and expressive being in what is an unprecedented vision of humanity for an artist.

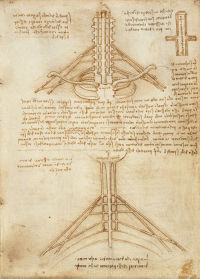

- Diagrammatic drawing illustarting how sight works The Royal Collection © 2005, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

- Diagrammatic drawing of the brachial plexus The Royal Collection © 2005, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

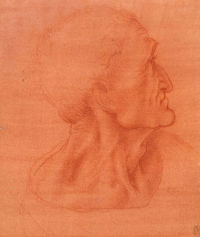

- Study for the Last Supper (head of Judas) The Royal Collection © 2005, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The seat of the soul

Leonardo’s conception of the neurological functions of the body provided the foundation for his artistic and scientific philosophy. In the Diagrammatic drawing illustrating how sight works, sensory information gathered in the Imprensiva travels to the sensus communis where fantasia (imagination), intelletto, and most importantly, the human soul reside. Elsewhere, Leonardo labels the sensus communis as volontà - voluntary action or movement that includes overall motion such as walking or running, and extends to small details of expression, such as the raising of an eyebrow. The sensus communis therefore, not only had receptive and analytical roles, but also performed the dynamic function of transmitting the commands for human motion.In his Diagrammatic drawing of the brachial plexus, Leonardo illustrates a system of “neurological plumbing”, whereby motor impulses are transmitted from the brain throughout the body via the spine. Tubular chords carry commands and sensations from the brain to the limbs and command the movements of the muscles and sinews. Because the soul instigates all physical movement in the body, in paintings, the gestures and expressions of every figure must visually communicate the concetto dell’anima or the “motions of their mind”.

Leonardo advises that “if you wish to show a good man speaking make his attitudes fitting accompaniments for good words; if you have to portray a bestial man, make him with fierce movements”.

The Last Supper is a perfect demonstration of Leonardo’s obsession with the concetto dell’anima. His understanding of the nervous system, muscles and tendons, “which and how many nerves are the cause of movement”, is already evident in the surviving preparatory drawings for the heads of the Apostles, for example in the Study for the head of Judas. In the painting, the ebb and flow of movement along the table is the outward effect of the inner causes of motion and emotion, as the individual movements of each disciple speak the body language of their mind.

- Two busts of men facing each other © Soprintendenza Speciale Polo Museale Fiorentino

Reading faces

Legend has it that Leonardo searched Milan for expressive facial types to use for the disciples in the Last Supper. He stressed the importance of carrying a notebook at all times to record observations directly from nature to create an aide memoire of faces. In line with the age-old tradition of physiognomy, he also recommended to painters to use a physiognomic classification of features. “Noses” for example, “are of ten kinds”.Leonardo subscribed to the general view that the signs of the face show the nature of men, their vices and temperaments. Those who have facial features of great relief and depth are “bestial and wrathful men with little reason, and those who have strongly pronounced lines located between the eyebrows are wrathful.

In Two busts of men facing each other familiar types are juxtaposed in old age and youth. Both are “idealized” to enhance the contrast and to highlight a favourite theme of the transient nature of beauty – a mortal thing of beauty passes and does not endure.

- Mona Lisa, Photo RMN - © Hervé Lewandowski / Thierry Le Mage

- Study of a dragon The Royal Collection © 2005, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Emotions and Fantasia

For Leonardo, emotion was a “continuous quantity”. Ever-changing, feelings cannot be fixed at one point. In the Mona Lisa, he created the equivalent of a mobile face in painting. The physiognomic signs do not constitute a single, fixed definitive image. The features of the face are difficult to read, the corners of the mouth and the eyes veiled in a mist of translucent glazes, dissolve into shadow.According to Dante in the Convivio, the soul operates largely in two places, the eyes and the mouth. “These two places, by a beautiful smile, may be called the balconies of the lady who dwells in the architecture of the body, that is to say the soul, because she often shows herself there as if under a veil.” The unknowable motions of Mona Lisa’s mind as the product of her very soul do seem to be reflected in her face.

According to Leonardo, fantasia and intelletto also resided in the sensus communis. Fantasia was a sort of active, combinatory imagination that could combine and recombine sensory impressions to create new compounds.

Study of a Dragon illustrates how realistic monsters could be created on the basis of knowledge of real animal anatomy. The concept of fantasia was already well established as a valuable artistic quality prior to Leonardo. The Florentine inventor and architect Antonio Filarete, for example, was well known for his ability to create fantasy buildings and ingenious allegories. But Leonardo’s vision of the imaginative faculty as an integral part of the inner senses was unique. It gave artistic invention the status of a scientifically recognized process of the human mind. It also gave artists a divine power to fabricate their own universe.

- Two skirmishes between horses and foot soldiers © Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, Polo Museale Veneziano

- The Sea God Neptune commanding his quadriga of sea horses The Royal Collection © 2005, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

From imagination to image

The importance of an artist’s creative faculty in Leonardo’s philosophy had a profound effect on his approach to compositional drawing. He advised that an artist must “first strive in drawing to give to the eye in indicative form the notion and invention made first in your imagination, subsequently taking away and adding on until you satisfy yourself”.The surviving tiny sketch of Two skirmishes between horses and foot soldiers are a perfect demonstration of his creative method. Beginning with “the invention made originally in your imagination”…”composing roughly the parts of the figures attending first to the movements appropriate to the mental motions of the protagonists involved in the narrative.” The definition of individual parts must be preceded by the fluent search for narrative force in the composition as a whole.

In the preparatory sketch for The Sea God Neptune commanding his quadriga of sea horses the fluidity of Leonardo’s creative process is equally astonishing. He freely creates forms inspired by Classical antiquity to create a coherent composition. Some of the rapidly worked black chalk lines emphasise key elements. Others suggest alternative poses, performing a creative role in their own right in the emergence of the most effective composition.

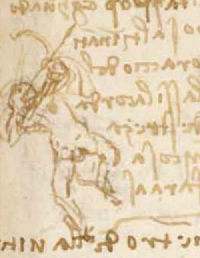

- Codex Forster, Book 1 Fol 44r, detail © V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum

- Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo – The Martyrdom of St Sebastian © National Gallery, London

Leonardo's revolution

Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists of 1550 conceded that Leonardo had instigated a revolution in the realm of art. By that time, Leonardo’s concept of the human figure as the primary vehicle for expression had become an ideal for all Renaissance artists. But Leonardo’s revolution was not merely a question of style. It was an entire reform of the creative procedures of the artist, based on the most profound understanding of nature.A tiny archer, illustrated in the Codex Forster Fol 44r illustrates the point perfectly. The sketch accompanies a description of how “Someone who wishes to draw back his bow…must set himself entirely on one foot, lifting the other so much higher than the first that it makes it necessary to counterpoise the weight which is thrown over the first foot”. When he wishes to let go of the bow “he suddenly and simultaneously leaps forward and extends his arm and releases the bowstring”.

A comparison between Leonardo’s archer and an archer from Antonio Pollaiuolo’s The Martyrdom of St Sebastian, painted in the 1470s, indicates the extent of the revolution that is Leonardo’s art.

See Also

Browse

Diagrammatic drawing illustrating how sight works

Diagrammatic drawing illustrating how sight works

Diagrammatic drawing of the brachial plexus

Diagrammatic drawing of the brachial plexus

Study for the Last Supper (head of Judas)

Study for the Last Supper (head of Judas)

Two busts of men facing each other

Two busts of men facing each other

Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa

Study of a dragon

Study of a dragon

Two skirmishes between horses and foot soldiers

Two skirmishes between horses and foot soldiers

The Sea God Neptune commanding his quadriga of sea horses

The Sea God Neptune commanding his quadriga of sea horses

Codex Forster I, II and III

Codex Forster I, II and III