The eye

"The eye, the function of which is so clearly demonstrated by experience, has been defined until the present time by a great many authors in a certain way – but I find it to be completely different."

- Mona Lisa, Photo RMN - © Hervé Lewandowski / Thierry Le Mage

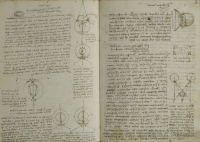

- Diagrammatic drawing illustrating how sight works, The Royal Collection © 2005, Her

Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The window of the soul

For Leonardo as an artist, the eye was tremendously important. He believed that the eye was “the window of the soul” and the most important of the senses by which we experience the natural world.Have you ever wondered how sight works? We now know that light enters the eye and is bent or refracted by the cornea through the pupil. It then passes through the lens, which completes refraction by focusing light onto the retina. The retina changes the light into electric impulses that are carried through the optic nerve to the brain where the image is interpreted.

Of course, in Leonardo’s time, sight was something of a mystery. Little was known about the anatomical structure of the eye. It was difficult to dissect. When cut into, it collapses and the lens takes on a spherical shape. Leonardo tried boiling his specimens but this distorted the shape of the lens and detached it from the retina. Faced with such difficulties he applied logic to the problem, mainly through drawing geometric diagrams and by studying optical effects.

Leonardo believed that the eye was a geometrical body, comprised of two concentric spheres. The outer he referred to as the “albugineous sphere” and the inner as the “vitreous” or “crystalline sphere”. At the back of the eye opposite the pupil is an opening into the optic nerve by which images were sent to the imprensiva in the brain, where all sensory information was collated.

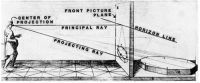

- Representation of Alberti's window. Engraving (modified) from G B Vignola, Le due regole della prospettiva practica, 1611

Visual power

Leonardo believed that sight was governed by the principles of geometry. The traditional view was that “Species” or rays of light were thought to project from the surfaces of all objects. These travelled to the eye and through the pupil to meet in a point in the eye to form a “visual pyramid”.The most remarkable aspect of Leonardo’s approach to the study of optics was his willingness to reassess his own ideas and the ideas of his predecessors. By 1508 he developed a more complex notion of how the eye functioned. Realising that the visual pyramid could not literally terminate in a single point, he identified a finite “area” for “visual power”, the location of which was unspecified. This allowed him to explain various phenomena such as why a small object like a sewing needle placed in front of the eye does not prevent us from seeing objects behind it, as it would if the eye perceived from a point.

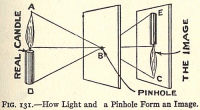

- The Pinhole camera and camera obscura principle, illustrated in The Boy Scientist, 1925

- Ms D Fol 3v-4r - On the human eye: dilation of the pupil. Photo RMN - © René-Gabriel Ojéda

I am a camera

Leonardo made an important contribution to the study of optics when he realized that the eye and its pupil operated like a camera, in that images were reversed and inverted when they entered the eye. However, unable to accept that images are received as such by the senses he explained their re-inversion within the eye, he invented a second point of “intersection” by which they were righted. It was not until 1604 that Kepler realized that inverted images were received on a concave retina.Leonardo also noticed the effects of bright light on the eye. Why is it he wondered, that the eye located in a bright place sees darkness inside a house, when on moving into the house there is light enough to see? The dilation of the pupil had been noted in Greek antiquity and medieval Islam. But Leonardo not only gave a fuller description of the circumstances under which the pupil varies its size, but also properly understood the cause as the intensity of light.

- Fire juggling

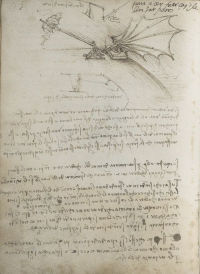

- Ms B Fol 88v - Design for a flying machine or catapult. Photo RMN © René-Gabriel Ojéda

- Fol 8r - Studies on the flight of birds © Biblioteca Reale, Torino

"Errors" of sight

Inspired by Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham), an 11th century Islamic philosopher and pioneer of the study of optics, Leonardo investigated certain “errors” of sight. He noted how a chord which is in rapid movement appears to be doubled, as “when a knife is fixed at the top of it and pulled forcibly to one side and released, causing it to shake back and forth”. Also how objects in rapid motion appear to be transparent and “will never obstruct the object behind the body that is moving”, because every object that moves with speed “tinges its path with a semblance of its colour”.If you move a lighted brand with a circular motion it will appear that its whole course is a flaming circle. This, he explained, is because the imprensiva (senses) is quicker than judgement, and as such a result of mental processes and not physiological optics.

Velazquez was the first artist to produce the effects of the “pseudo transparency” of objects in rapid movement in his painting Las Hilanderas. Leonardo never attempted to do so in his painting, but sometimes he used line to portray the effects of movement in his drawings in a way that was innovative for the time.

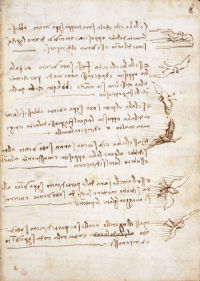

On Manuscript B Fol 88v rapidly applied parallel hatching conveys the dynamic movement inherent in the experiment illustrated and on Fol 8r from the Codex on the Flight of Birds the directional winds on which the birds glide and manoeuvre.

- Sunlight behind trees © Jeff Werner

Colour, light and shade

In his study of optical effects in nature, Leonardo made astute and beautifully expressed observations regarding our perception of light, shadow and colour.Noting the effects of extreme glare, he remarks that objects appear to be “eroded” by brilliant light behind, as when the sun is behind a tree, the “branches are so diminished that they remain invisible”. His observation of green shadows cast by ropes and ship-masts on a white wall seems to pre-empt Goethe’s discourse on coloured shadows of 1792. But Leonardo understood them as the result of reflections from the “hue of the sea” opposite and not as a phenomenon of light itself.

Of all the optical phenomena observed, Leonardo’s study of light and shade had the greatest impact on his work. In his paintings, he repeatedly contrives the setting of dark boundaries against lighter ones and vice versa to enhance the sense of three-dimensionality of overlapping forms. Later artists including Vermeer, De Hooch and Seurat also employed enhanced edge contrasts to achieve similar effects of modelling.

Leonardo’s lack of knowledge of Latin may have hindered his study of optics, but his belief in the validity of experiment and observation led him to important observations and conclusions. He correctly made a distinction between peripheral vision and central vision, and he was probably the first to write about stereoscopic vision (the way the eyes work together to gather information about an object).

Ultimately the problem of sight could not be solved by an ingenious empiricist, even one as brilliant as Leonardo! Yet his willingness to investigate phenomena beyond the limits of the painter’s powers is truly admirable, and goes well beyond the demands of painting.